How to Flip Texas by 2030

The District Action Council Model Presents an Opportunity to Turn Texas Blue for a Generation

Texas Democrats are tired.

The Texas Democratic Party has lost every statewide race since 1994.

The Texas Senate has been in Republican hands since 1996.

The Texas House? Since 2002.

Why do we keep losing? Get a focus group of ten Democratic activists in a room, and you’ll get fifteen responses:

It’s a messaging problem! We aren’t speaking to rural communities!

It’s a messaging problem! We’re not speaking to people in the cities!

We’re too liberal!

We’re not organized!

We need to speak about kitchen table issues!

We need to engage Gen Z!

The state is too gerrymandered!

It’s because of voter suppression!

Greg Abbott is suppressing the vote!

While all of these challenges may (or may not) have merit, I would contend that one of the major overlooked causes that can truly be solved and agreed upon is the electoral organizing model… which is currently more broken than Greg Abbott’s moral compass.

Campaign-Driven Campaigns: Our Broken Organizing Model

“I am not a member of any organized political party. I am a Democrat.”

-Will Rogers

Here is how most electoral organizing works:

The incumbent party in a given seat engages in what equates to a natural around-the-clock campaign schedule. They give speeches in their district and at the Capitol. Their staff puts out press releases about recently filed bills. They take pictures and send them out through their government-sponsored newsletters. They can call any media station, submit an editorial to any newspaper, and secure earned media with little effort. They are in constant campaign mode by virtue of their position.

The non-incumbents—in Texas, that’s usually us, folks—campaign much differently. Usually, the community follows the lead of the campaign. A few diehards (like me and some of you) get involved in the primaries. Still, most Democratic door knockers are basically in hibernation until the dust has cleared and the primary voters have nominated their candidates. Suppose any issue-based groups become interested in the race. In that case, they have to either pick a side in the primary, work in isolation or take a pass because the district is simply too dadgum complicated to work on.

Then, finally, the ground game effort begins, led by the victor in the primary. Activists who met through hand-to-hand political combat during the primary are expected to bury the hatchet immediately and bond on the spot so they can rally around the winner. Insights into specific areas and the needs of disengaged or persuadable voters are collected on the fly.

If the candidate wins, the people who supported it become the fanbase of the newly elected official. If it fails, the campaign disbands, the community disconnects, and we repeat the process all over again two years later. All of the infrastructure, energy, connections, and other resources collected and built from the previous campaign fell apart. Activists who were involved in the last cycle often decide it just isn’t worth it this time around; they’ve got lives to live, and neither their time nor the gasoline that powers their vehicles is free. Next time, they may do something else instead of knocking on doors, making calls, writing postcards, protesting, or writing checks to campaigns.

Like a sandcastle, any infrastructure or activist energy from the cycle simply blows away.

The good news is that no matter what your concerns are as a donor, precinct chair, operative, activist, or reliable voter, there’s a better way to do things, a model that has worked in other states and individual districts to change the dynamic.

This model can support us in winning down-ballot and unlocking opportunities to sweep statewide seats.

More importantly, it can equip us with the infrastructure we need to win long-term victories and even hold leaders accountable after they enter elected office, thus building a better world (which is the point of winning elections in the first place).

District Action Councils: A Model for High Octane Organizing

District Action Councils are coalitions of grassroots organizations, local Democratic clubs, labor unions, and PACs (Political Action Committees) working together and sharing a common, web-based calendar of events designed to engage voters to flip seats.

District Action Councils bring everyone to the table to discuss their agenda in a way that allows them to unify their power while still focusing on their individual interests.

As an activist once told me, “Groups in coalition march in their own direction but strike as one.”

District Action Councils empower coalitions to strike more effectively.

Why?

District Action Councils empower groups to come together at a local or state level far before the primary ever takes place.

As a result, progressive groups can start building infrastructure, raising money, messaging their neighbors, and forming relationships on peaceful, collaborative ground, with a headstart on the election.

If issue groups become interested in the area, they don’t have to contact primary campaigns or the local nonpartisan neighborhood club. They also don’t have to move forward on their own, risking major organizing mistakes by entering neighborhoods they know nothing about.

Instead, these issue groups and grassroots activists can contact a growing table of community leaders who know their neighbors and have an understanding of local culture and institutions, including the physical geography of the area, the weather, neighborhood influencers, legal restrictions, and other key elements that would be overlooked on a shorter timeline.

Members of District Action Councils meet one another based on common ground: they all want to make a difference and win the general election. They may differ in the primary, and perhaps things will still get heated. Still, there is more room for healing after the primary than there is in a traditional organizing model because the members of the council meet under circumstances of peace (pre-election organizing) rather than war (primary elections).

If the candidate wins, the community can hold them accountable and continue to apply pressure regarding issues they care about. If the newly elected official does a good job, the elected will have even more support than your average incumbent when they run for reelection.

If the candidate loses, the District Action Council can stay together, advocate, and continue to build on their progress until the next election cycle, when either that same candidate or a new primary winner can take another shot with an electoral infrastructure that is stronger than ever.

Has Texas tried District Action Councils?

Kind of… but not really.

Over the last six years, I have heard a lot of folks in Harris County discuss the need for us to coordinate and work together more. From 2016 through 2020, our county party did a good job of holding meetings that brought activists to the table. During that time period, several rolling coalition meetings brought groups together on various issues, such as democracy concerns or criminal justice reform.

In 2018, a large group of leaders met up, thanks to Sri Preston Kulkarni and RideShare2Vote, to discuss exactly the kinds of issues that District Action Councils are intended to solve… but follow-up meetings with all parties were infrequent. Leaders never quite closed the loop on some of the more specific operational mechanics that might have pushed people across the finish line. This problem persists across Texas, where communities continuously build up and tear down efforts based on electoral cycles.

The best example in Texas of a coordinated effort that is similar to a District Action Council was the race for Texas’ 7th congressional district (TX-07), which had been in Republican control since 1966 when George H. Bush took the newly drawn district out of Democratic hands.

By 2016, the incumbent Republican, John Culberson, had been in office for eight terms. A strong Trump supporter and inflammatory rightwing rep, Culberson failed to realize that his district had been slowly shifting ideologically from the right toward the center.

Several groups became heavily engaged long before a nominee was selected. Notably, Swing Texas Left and Indivisible Houston coordinated to host forums, execute blockwalks, protest, and engage in other communications efforts to inform the community of Culberson’s failure as a representative. These efforts led to enhanced turnout for events and impactful ground games on par with some of the most impressive efforts in recent American history.

In spite of a combative seven-way primary, volunteers rallied to support the nominee Lizzie Fletcher. In a district Culberson had won in the previous cycle by nearly 13 points, Fletcher won by five. The first group she thanked after winning was Swing Left.

The efforts of the grassroots in TX-07 had positive residual impacts both statewide and in down-ballot and inter-district areas. Fletcher won the race with nearly 128,000 votes, the overwhelming majority of which were in Harris County.

Many of the areas of focus for Swing Left TX-07’s ground game were in traditionally overlooked neighborhoods, such as my precinct, which has nearly 7,000 residents in more than fifteen apartment complexes. Many of those voters were engaged for the entire Democratic ticket, which meant extra votes for Harris County judicial candidates, including Lina Hidalgo, as well as statewide candidates like Mike Collier and Beto O’Rouke.

It would be silly to argue that the activists in the 7th were the only thing that helped the county candidates win, or the statewide candidates get close; such a claim would vastly discount the efforts of grassroots activists and down-ballot candidates who put in the work to help themselves win in other parts of the county and state. But the TX-07 activists definitely contributed significantly to victory.

Rightwing organizers have also used a model similar to District Action Councils in Texas. The Texas Tea Party and its affiliated groups have used a similar strategy for years.

A former Tea Party activist-turned-Indivisible member out of Dallas once told me that various groups would connect on a regular basis and plan meetings to pressure local electeds.

“We were effective because we went to every county judge and asked whether or not they would let Obama take our f***ing guns,” he said. “Then, when election time came around, we’d coordinate to knock on doors and sweep every seat we targeted.”

In other words, conservatives have been doing something like this in Texas for a long time, with pretty good success.

Where have District Action Councils worked?

Perhaps the best and most closely detailed example of a successful District Action Council comes from California. While California may be a left-leaning state, the region on which the example is based is far more purple, not unlike TX-07.

In the same cycle when Fletcher defeated Culberson, activists in Southern California successfully took on five congressional districts where flips were possible (CA-25, CA-39, CA-45, CA-48, CA-49), the largest mass pickup opportunity of congressional seats anywhere in the country.

As was the case in many other regions, activists formed tons of new organizational chapters (Indivisible, Sister District, Swing Left, etc.). They were all focused on similar goals but weren’t connected… at first.

A social activist in the area of CA-49 developed a plan to flip the district, then founded Flip, the 49th PAC. She brought together grassroots groups, SEIU, various Democratic clubs, and the San Diego Democratic Party. The CA49 Action Council began deep canvassing a year before the primary.

Around the same time, a group of Indivisibles in CA-33 started a subgroup called Swing SoCal Left, which focused on flipping all five SoCal districts. The organization started a community calendar and then sought out groups in the area with whom they could initiate meetings and introduce that calendar. Action councils were set up soon after in the other four districts, all of them launching canvassing in the context of community rather than the context of campaigns.

All of the councils focused on their own district but welcomed assistance from surrounding areas as well, tapping into the energy of activists from nearby safe seats who wanted to help.

The Action Councils were able to channel this energy appropriately. Oftentimes, outside help can fail to make an impact or even set back local efforts because outside activists are not acquainted with the area. Thanks to the Action Councils, outsiders could pitch effectively, and in-district activists could leverage reinforcements, a win-win for all involved.

The Action Councils did not always agree on the issues; infighting is an inevitability of progressive coalitions. But through a shared calendar, a regular communication channel, and consistent sit-down meetings, these groups could target their energy appropriately, stay focused on their goals, and win.

In 2018, the Democrats took the House by gaining 41 seats. More than 10% of total pickups came from this one effort: all five swing seats in Southern California turned blue, transforming a congressional region that had previously been ⅔ Republican into one that was 100% Democratic.

OK, but that’s California. This is Texas. Would District Action Councils work here?

Yes! The TX-07 effort demonstrates that District Action Councils can work in Texas. Similar models have worked in other areas of the country:

In 2017, Jon Ossoff lost the special election for Georgia’s 6th Congressional District to Karen Handel by more than 9,000 votes, a spread of 3.6% in the election. Despite Ossoff’s loss, grassroots groups stayed committed to booting Handel from office. In the very next election cycle in 2018, Lucy McBath vanquished the incumbent by more than 3,000 votes.

In 2016, Arizona infamously voted for Trump by approximately 90,000 votes or 4% of the population. In 2020, grassroots activists were able to deliver Arizona for Biden by about 10,000 votes, thanks largely to the hard work of Latino activists in the Mi AZ coalition. Mi AZ included groups like Lucha, which formed in response to the Show Me Your Papers law. The effort increased Latino turnout in key precincts by up to 20%. You can read about it in more detail here. The campaign also heavily benefitted from the work of Native American activist organizations such as Four Directions and the Rural Arizona Project, who busted barriers to voting that are common on reservations. These groups coordinated heavily throughout the cycle.

In 2016, Michigan infamously voted for Trump by about 10,000 votes, partly due to low Black voter turnout in Detroit. Groups like Detroit Action and We the People worked diligently through the next cycle and the one following, increasing Black voter turnout to secure victories throughout the state and flipping Michigan back into the Democratic column for the presidential race.

You will notice that all three of these cases featured major shocks to the system that lit a fire under activist efforts:

Arizona passed SB1070, a bill that empowered racial profiling and mass deportation of immigrants, a precursor to Trump’s DHS policy on family separation.

Michigan suffered through the Flint Water crisis and the auto industry's collapse.

Georgia underwent one of the most significant slides toward anti-democratic fascism of any state in the country thanks to Brian Kemp running his own election for governor.

Each of these issues spurred community conversations, and that’s without considering the massive wave of people who became activists in response to the Trump Administration.

Texas has had very real and clear trauma of its own for a generation:

Corporate polluters have poisoned our waterways for years in virtually every region of the state. Recently, polluters tried to send toxic water from the Ohio train derailment to Houston; a move only blocked when the EPA got involved.

Greg Abbott has been using migrant families and Latino communities as political pawns for decades. He has bussed them to random locations in other states, sent the Texas National Guard to the border, and installed buoys and razor wire along the border, all part of an ongoing campaign of deadly political stunts. In 2017, he signed a Show Me Your Papers Law which enabled law enforcement officials to demand proof of immigration status regardless of whether a crime was being committed. The law also coerced local law enforcement into pledging assistance to Trump’s ICE department, which oversaw the deaths of multiple migrants in Texas facilities. The outcome? A decrease in reporting of domestic abuse, all as the result of a fear of deportation.

During a winter storm, our power grid failed in 2021, killing hundreds of Texans. It still hasn’t been fixed. The grid remains vulnerable to failure in both extreme cold and extreme heat.

Multiple bills demonizing gay and trans kids passed the Texas Legislature in 2023, including bans on drag shows and gender-affirming care. These bills were passed with full knowledge that trans kids face a higher risk of suicide.

DPS recently militarized Austin policing as part of a partnership with the city. They ended up harassing Black and Latino Austinians and pulling a gun on a 10-year-old kid.

Multiple mass shootings have taken place over the last decade. 2023 was particularly bloody. In 2022, 19 kids and two teachers were shot at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde. In 2019, a shooting in El Paso killed 23 and injured 22. The El Paso gunman left a manifesto decrying “Hispanic invasion,” parroting language from the Trump White House’s common propaganda practices.

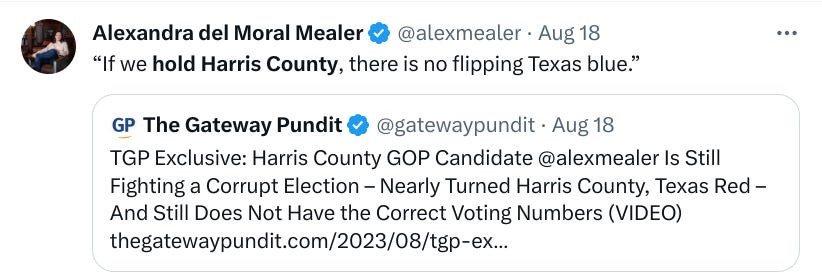

In the 2023 legislative session, the state explicitly targeted Harris County’s right to govern and hold free and fair elections. Senate Bill 1750 eliminates our county’s nonpartisan election administrator’s office. Senate Bill 1933 allows the state to take over county elections if someone, like a candidate or a political party leader, lodges a complaint. These bills were written to apply only to Harris County, which is no accident. Several Republican candidates, including Alexandra Mealer, are attempting to pull a coup through the courts after our 2022 election. Mealer has been nakedly political in her interests in the case, using the phrases “Hold Harris County, Hold Texas” and “Hold Harris County to keep Texas from turning blue” in fundraising pitches to support her case. Mealer has gone so far as to peddle that narrative to Gateway Pundit. This known conspiracy outlet supported overturning the 2020 presidential election and a wide variety of other false narratives related to vaccines, voting, and school shootings.

Houston Independent School District, one of the largest districts in the country, has recently gone through takeover by the state. In the short period of time that Texas has colonized our school district, they have appointed a board of managers that includes a member who lost her election to one of our duly elected trustees; turned libraries into discipline centers, appointed a charter CEO as superintendent who recently coerced kids into helping him sell a hollow story at a district-sanctioned event…

And that’s the tip of the iceberg of any of these individual issues. I could go on and on about trauma from storm damage, lack of healthcare, further colonization of counties and cities, abuse of people with disabilities, a massively racist system of incarceration, lack of housing, depressed wages, and plenty more, but you get the idea. No matter how you slice it, Texas has had its fair share of shocks to the system.

Where do we start?

There are 149 seats in the Texas House. The Democrats currently control 64, which means the Democrats have to pick up 11 seats (assuming all of those Democrats caucus together and we have no sellouts… so it may be worth it to get a few more, just for insurance).

There are 17 seats that can be flipped if we can switch ten percent of the vote or turn out enough new voters to make up that 10%. We have until 2030 to make that happen; in that session, Texas will draw new maps, and a Republican majority will want to gerrymander Texas for another generation.

Let’s take a look at those seats:

If you’re looking at the board and thinking, “That looks pretty hard,” let me just say: that you have a point. If the proverb, “Nothing worth doing is ever easy,” were a visual aid, it would be this chart.

But there are a lot of reasons why the margins alone are misleading.

First, ten of these seats are within a 15-point range, which was the exact swing TX-07 activists achieved to topple John Culberson. And every single seat features a range smaller than the swing in vote totals that allowed Lina Hidalgo to defeat Ed Emmett for Harris County Judge. And that’s if you skip a cycle, as Emmett did not even have a challenger in 2014.

Second, some of these reps are absolute ninnies. They make terrible decisions. They have sex and hate speech scandals. They engage in election fraud. They hire extremist Christian Nationalists as staffers. They carry water for the Texas Republican Party in a state that is slowly shifting in its attitudes and behaviors. They are thoroughly beatable.

Third, we have had our shocks to the system. People are pissed off, and they’re not going to take this stuff anymore. As organizers, we have the opportunity to lift people up so they can channel their anger and energy into payback for the people who hurt them.

Fourth, we have more than one cycle to make this happen. Some seats may take time to flip, but all of them are flippable.

Fifth, we have a new model to try out that can specifically benefit our efforts through a regional focus. These 18 seats are in nine counties. Several counties have three seats, so we can harness collaboration and pick up energy from nearby activists to assist in knocking reps out of office.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly: no one is tougher than Texas activists. We love our families, our communities, and our homes. We have been through major challenges and continued to fight.

With the right strategy, we’ll be unstoppable, no matter what any MAGA-brained street Nazi or Christian Nationalist Lt. Governor has to say about it.

Let’s save the world.

If we change Texas, we can change the nation.

If we change the nation, we can get a handle on democracy and climate change.

If we save democracy and reverse climate change, we can save the world.

Let’s save the world.

You can help the GAP Network’s District Tables by volunteering or donating to our efforts.

Sounds like it's typically been a reactionary, fragmented catch-up strategy that lacks continuity. The new strategy would be more proactive, unified across space (geography) and continuous across time. One less dependent on star-players (candidates) and stronger systemically (organization). To reference Taleb, building an organization that is more anti-fragile, meaning it expects some loss but becomes stronger because of it (vs. a fragile organization that disintegrates after loss).

Excellent ideas here!